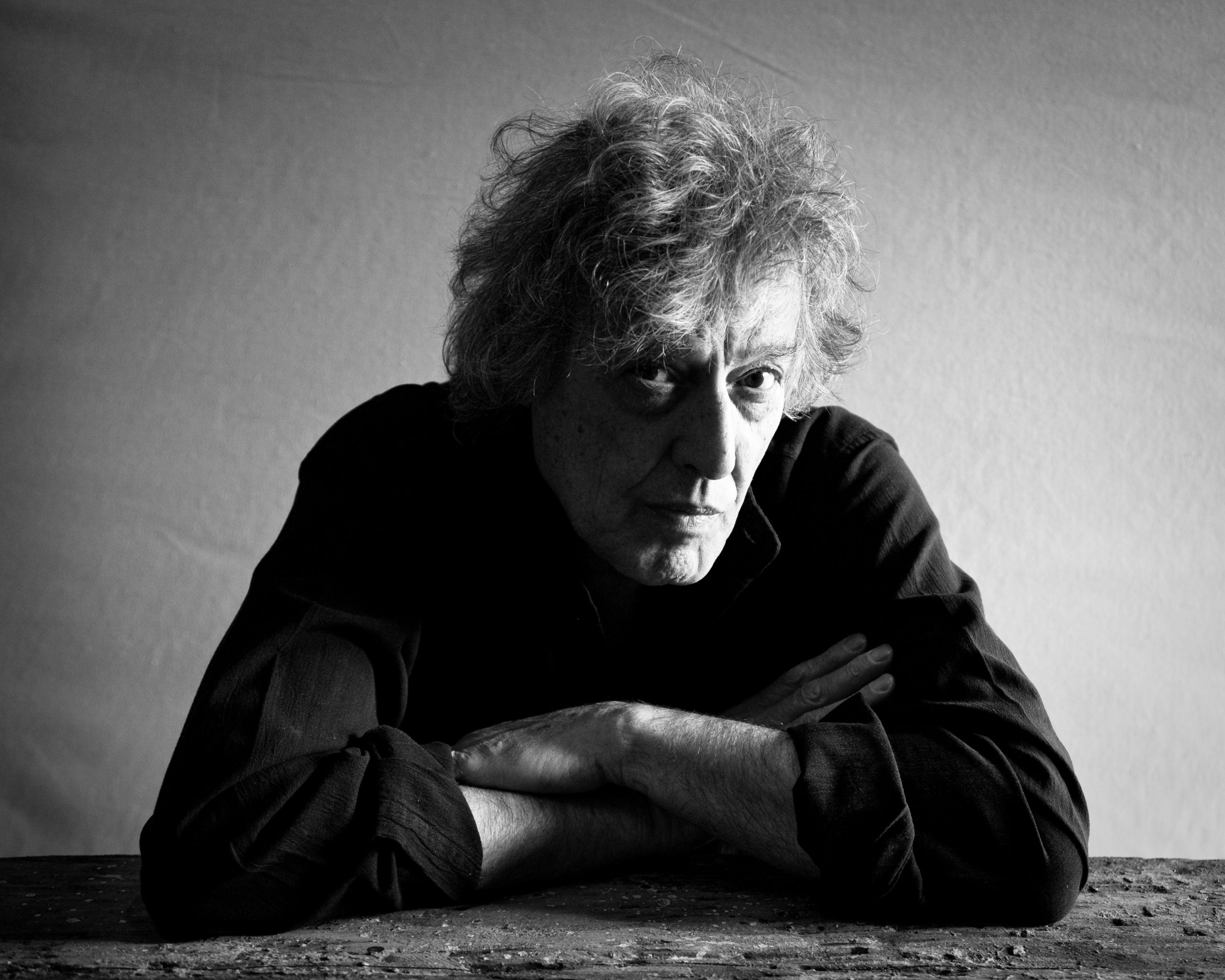

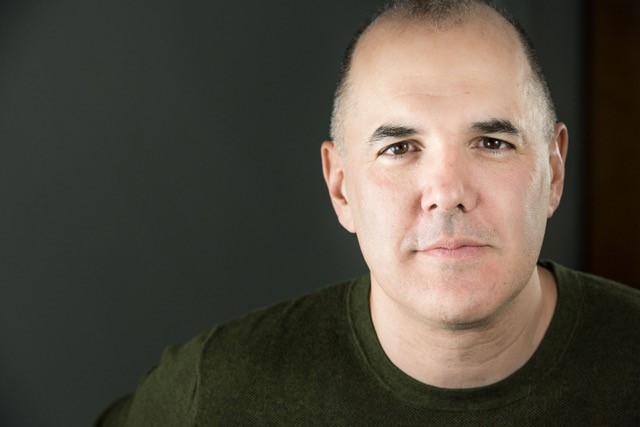

John Kingsley Orton was born on January 1, 1933 in Leicester, England to a working class family that valued neither affection nor emotion. Largely self-educated (he failed at school but avidly pursued reading and classical music) the adolescent Orton was drawn to the fantasies and possibilities of theatre, and developed an ambition to act. His aim, he wrote, was ‘to be connected with the stage in some way, with the magic of the Theatre and everything it means. I know now I shall always want to act and I can no more sit in an office all my life than fly’. In 1951, Orton was accepted to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, where he met Kenneth Halliwell, a fellow student and former classics scholar seven years his senior. Their tumultuous marriage lasted sixteen years-the rest of their lives-and saw a major reversal in their relationship from which Halliwell, ultimately, would never recover. Depressive, egotistic, abrasive, Halliwell was the intellectual who invited his younger lover to share in his dream of becoming a successful writer. Orton, initially an insecure actor, soon developed the unique voice that brought him extraordinary success and earned him praise as the most successful comic playwright since Oscar Wilde. From 1953 to 1963, Orton and Halliwell jointly wrote a series of unpublished novels and plays. They also gained notoriety for a literary endeavour of a far different kind: stealing and defacing public library books in satirical ways. In 1962, both men were arrested and imprisoned for maliciously damaging more than 70 library books, including removing more than 1,650 plates from art books. By this time, however, Orton-who had begun to write independently from Halliwell several years earlier-was also beginning to achieve his first literary success. Soon after the BBC accepted a radio version of his script THE RUFFIAN ON THE STAIR in 1963, he embarked on the full-length play, ENTERTAINING MR. SLOANE, which would launch his career and acquired a literary agent, the legendary Margaret Ramsay. His writing, Lahr notes, took on a playful antic quality of a man who, now a 'criminal,' had nothing to lose from society. That sense of freedom spilled over into Orton's life as well as his art, particularly in the extensive, often anonymous, sexual encounters that are recounted in his DIARIES. Between 1964 and 1967 Orton completed his theatrical masterpieces, both farces: LOOT (which won the 1967 Evening Standard Award and Plays and Players Award as best new play of the year) and WHAT THE BUTLER SAW. Blazingly ferocious attacks on societal conformity and sexual guilt, the plays are inspired verbal and visual assaults on what Orton saw as the inadequacies of such institutions as the church and the law. On August 10, 1967, however, it all came to an end. Halliwell, increasingly jealous of Orton in their later years together, bashed his lover's head in with a hammer and then committed suicide by swallowing 22 sleeping pills. At the time, Lahr writes, Orton's death was more famous than his plays. But the years and our farcical history have reversed this situation. Nobody came closer than Orton to reviving on the English stage the outrageousness and violent prankster's spirit of comedy and creating the purest (and rarest) of drama's by-products: joy.