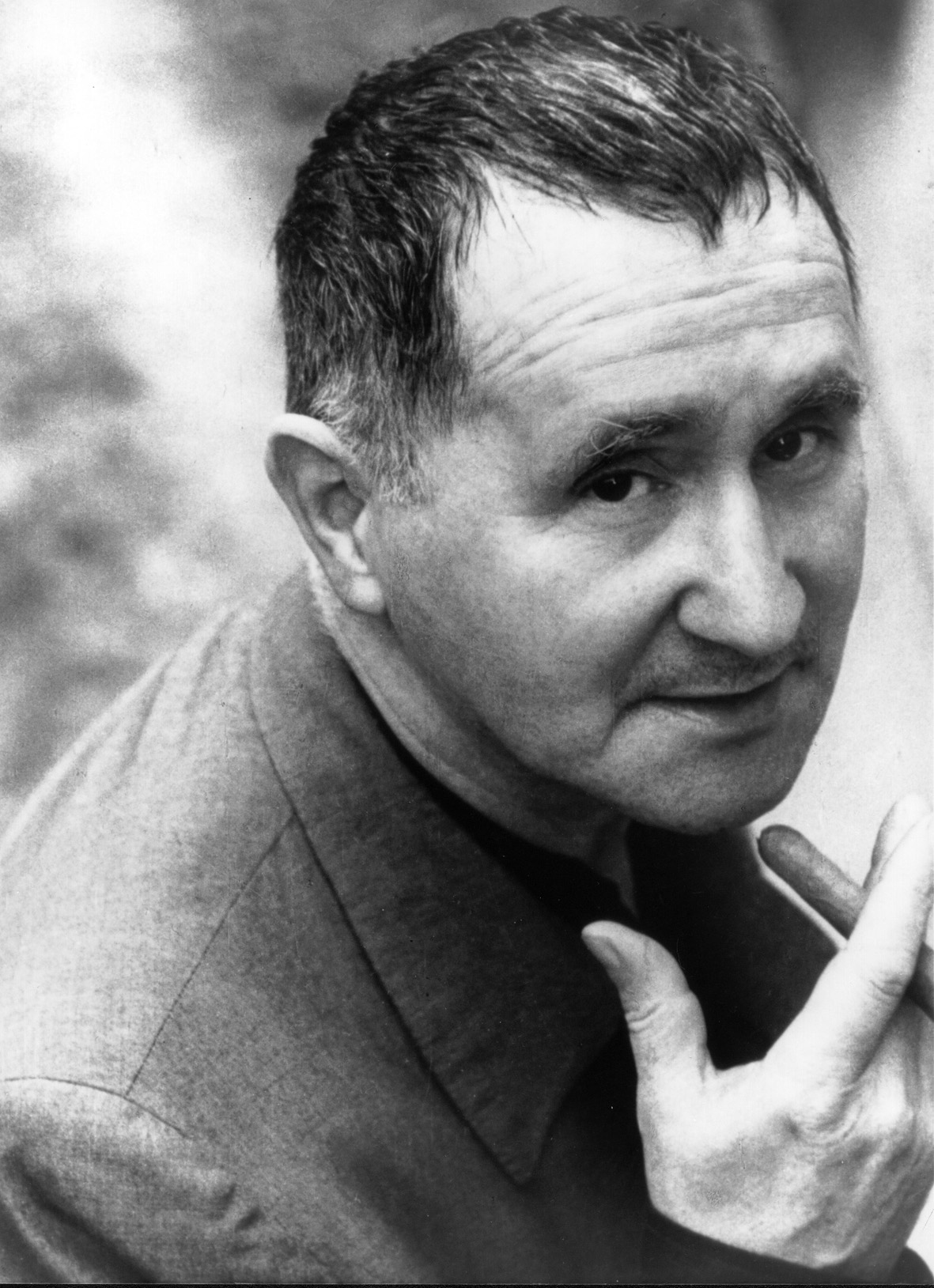

A poet first and foremost, Bertolt Brecht’s genius was for language. However, because this language is built upon a certain bold and direct simplicity, his plays often lose something in the translation from his native German. Nevertheless, they contain a rare poetic vision, a voice that has rarely been paralleled in the 20th century.

In his early plays, Brecht experimented with dada and expressionism, but in his later work, he developed a style more suited his own unique vision. He detested the “Aristotelian” drama and its attempts to lure the spectator into a kind of trance-like state, a total identification with the hero to the point of complete self-oblivion, resulting in feelings of terror and pity and, ultimately, an emotional catharsis. He didn’t want his audience to feel – he wanted them to think – he was determined to destroy the theatrical illusion, and, thus, that dull trance-like state he so despised.

The result of Brecht’s research was a technique known as “Verfremdungseffekt” or the “alienation effect”. It was designed to encourage the audience to retain their critical detachment. His theories resulted in a number of “epic” dramas, among them Mother Courage and Her Children, both a triumph and a failure for Brecht. Although the play was a great success, he never managed to achieve in his audience the unemotional, analytical response he desired.

Brecht would go on to write a number of modern masterpieces including The Good Person of Szechwan and The Caucasian Chalk Circle. In the end, Brecht’s audience stubbornly went on being moved to terror and pity. However, his dramatic theories have spread across the globe, and he left behind a group of dedicated disciples known today as “Brechtians” who continue to propagate his teachings.